Everything Under, Mark Požlep, 2025

Film Essay, 20’51”, 2025

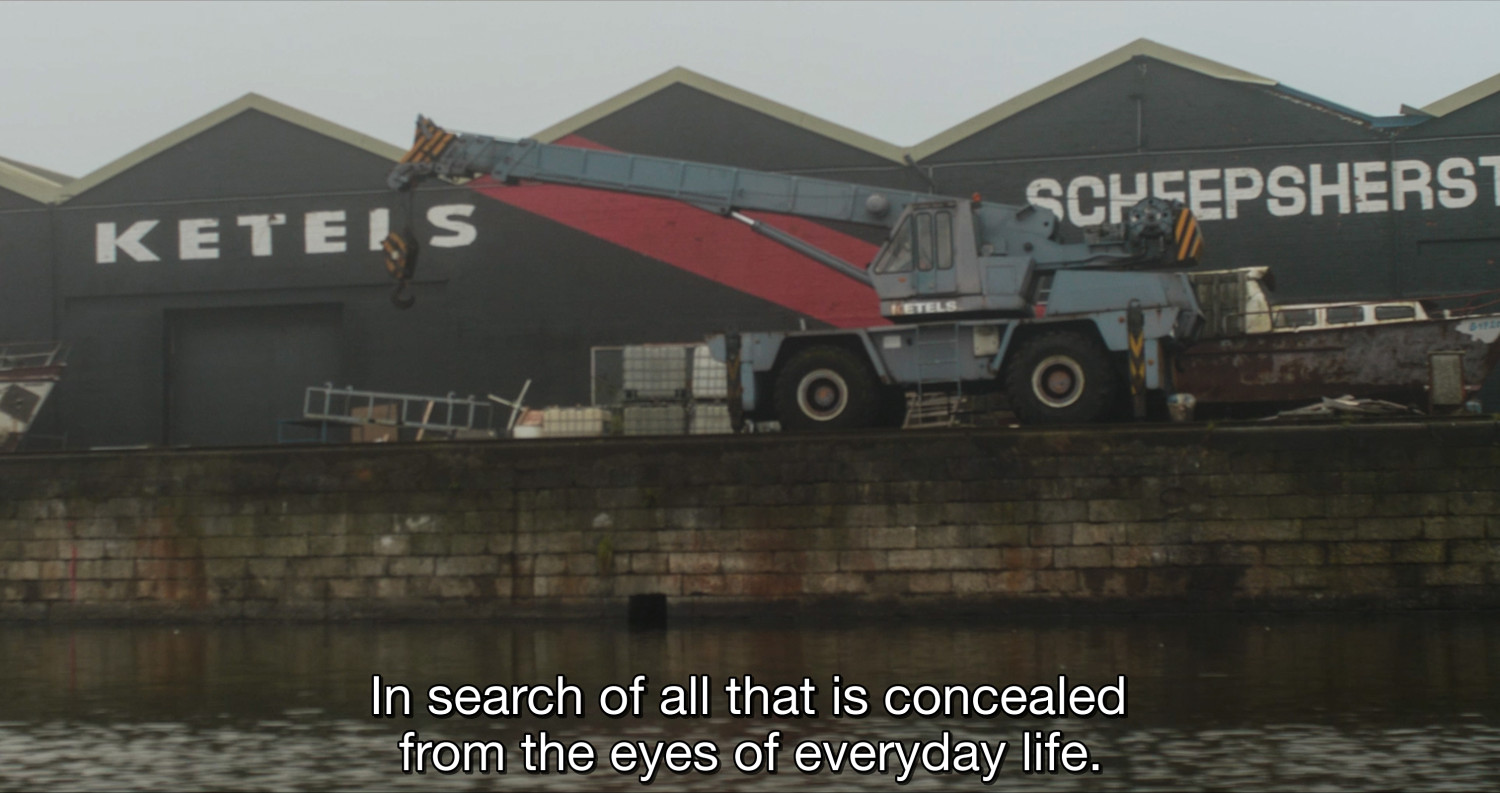

Everything Under is a boat, a journey, a film, a poem and a performance by Slovenian artist Mark Požlep. The film is a poetic stream of consciousness, a layered meditation that starts from Požlep’s exploration of the waterways of Ghent on his own hand-built aluminium boat.

Požlep has been living on a houseboat along the Ghent docks for a decade. He has seen the neighbourhood evolve from a rough area on the old docks where neighbours shared evenings around the campfire to a new neighbourhood with luxurious apartment blocks, schools, a coffee bar and a summer festival. The Roma have disappeared. Gentrification does not stop at the waterline. The mooring fees for houseboats at the new docks are on par with the high housing prices in the newly developed neighbourhood.

His exploration began out of nostalgia and curiosity. Požlep was born in socialist Yugoslavia, where the river regularly overflowed its banks, fearlessly claiming its place, and meant shared fun during hot summers. He wondered whether that kind of untamed life could still be found in or around the waterways of Ghent today.

The short answer? No. But read on.

Water and people have a long-standing relationship. Where there was water, people liked to settle. Water was there for us, in a relationship that implies a certain reciprocity. Those who settled soon forgot that rivers have a life that their own lives depend on.

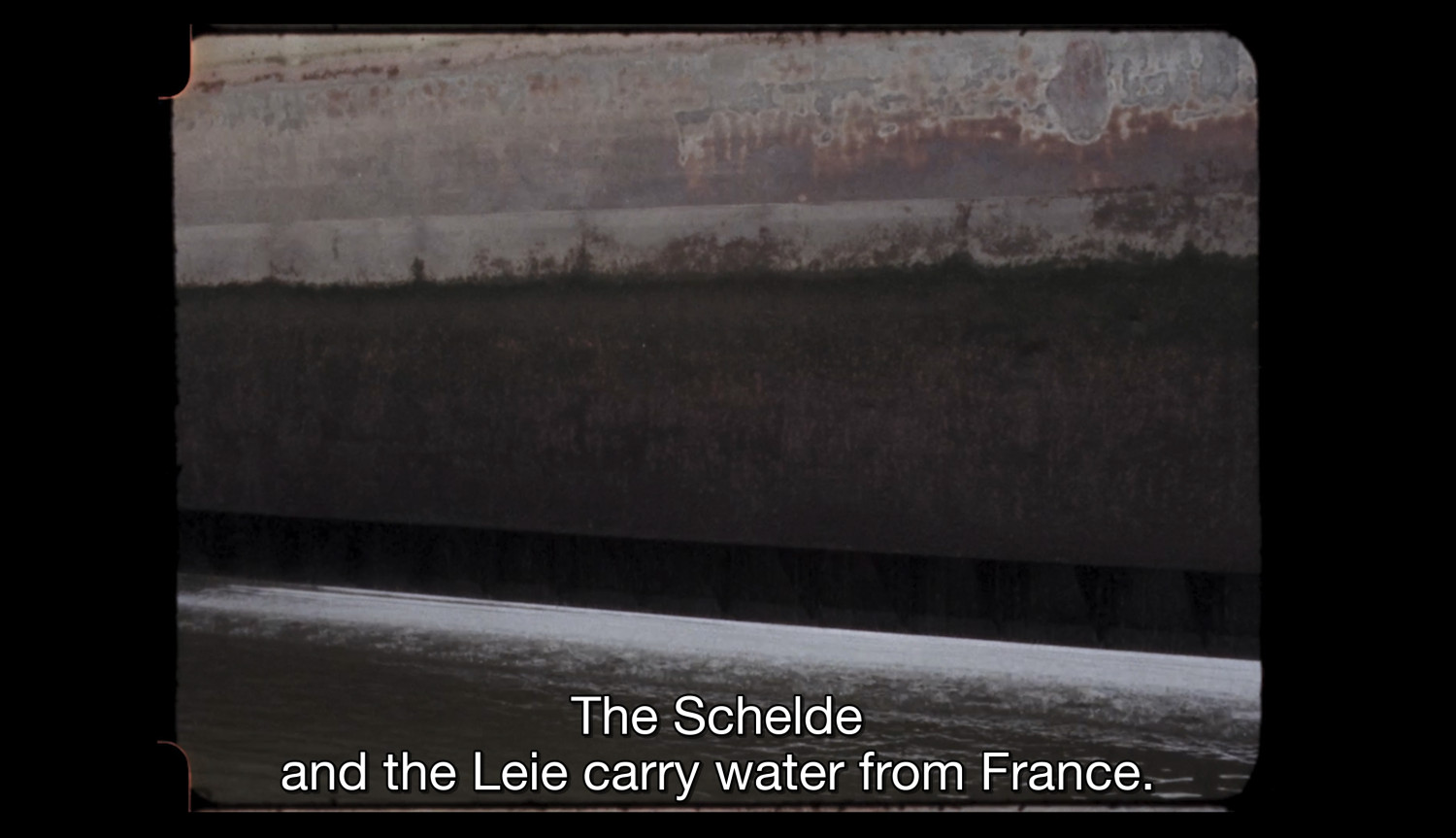

The First Water is the Body is the title of a poem from Natalie Diaz’s acclaimed collection Postcolonial Love Poem. The line is deliberately written in such a way that you don’t know which body the poet is referring to. The river in question is the Colorado River. ‘Aha Makav is the name of her people, the Mojave, who live in the region around the Colorado River. Translated into English, ‘Aha Makav means “the river runs through the middle of our body, the same way it runs through the middle of our land”. The Colorado River is the most endangered river in the United States. A body of water is a body politic that connects many bodies.

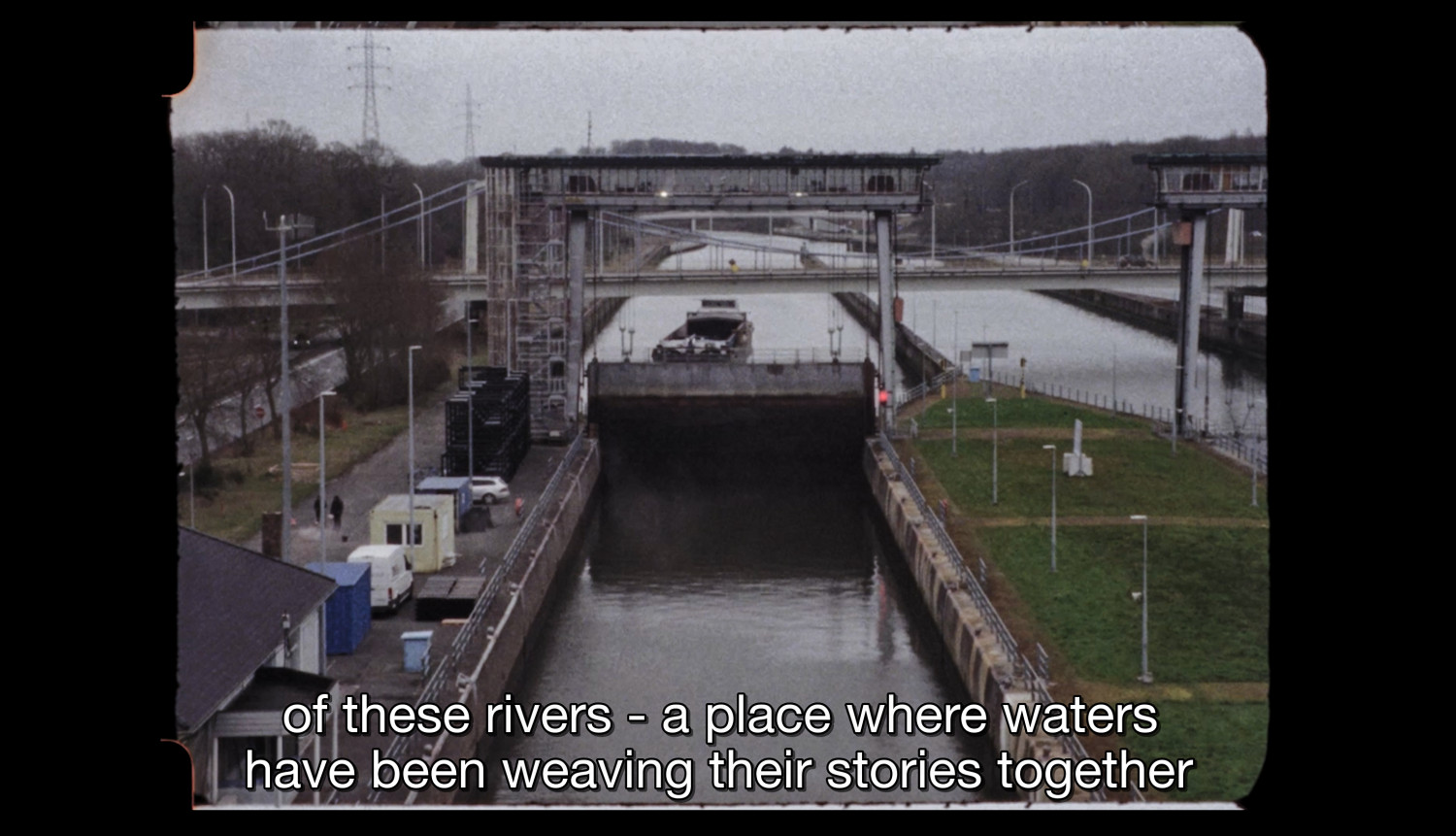

Ghent, founded at the confluence of the Leie and Scheldt rivers, long enjoyed the opportunities offered by the two rivers. From the thirteenth century onward, however, the city began to interfere in the waterways. The flourishing textile industry needed to secure a direct connection to the sea. The Lieve Canal was opened in 1269. In the sixteenth century, the Sasse Canal was dug. This was followed by the Bruges Canal (17th century), the Coupure (18th century), the Ghent-Terneuzen Canal (19th century) and the Ring Canal (second half of the 20th century). Canals, dams, dykes and locks had to channel the water in a way that met human needs. In our culture and our imagination waterways are mainly assigned the role of economic infrastructure. In most cities, more water flows than can be seen. Rivers are dammed to facilitate human traffic.

In Is a River Alive?, British author Robert Macfarlane describes how industrialised countries have made life of who surrounds us so quiet that the prevailing sentiment of our time is one of loneliness and isolation.

In search of places where he could experience the river in full vitality, Požlep felt the most awe at the locks in Merelbeke, where the Scheldt flows into the Ring Canal and pounds against the locks with full vigour—or is it protest?

“How to translate”, Natalie Diaz wonders, “not in words but in belief, that a river has a body, alive just like you and me, and that without it, life is not possible?” Can we remove the conceptual dams around our imagination, revive the world around us?

Revive in the sense of “to restore to life”, but also: “to renew the idea, using healing powers such as, attention, and love?”

Everything flows, as we have known since Heraclitus: time and rivers are never the same. Our imagination and the practices based on it influence our environment.

Here is a proposal, which is more of an old idea than a new one, based on existing practices and other cultures, but why reinvent the wheel? In Dutch, turn rivieren into a verb, meaning recognising and honouring the life of the river, understanding the intertwined life of the river and its surroundings. In English it becomes, riverance, a noun meaning reverence and respect for the life of the river.

It could benefit both our sense of loneliness and life in the river. Because are they really two separate issues?

Exhibition text _ Nele Buyst

Produced by Kunsthal Gent, Kunstencentrum VIERNULVIER, de Koer

Project was subsidised by Vlaamse Gemeenschap

Everything under, 2025

Project by Mark Požlep

Camera: Kobe Wens, Mark Požlep

Editing: Kobe Wens

Sound: Iris Van Geen, Kobe Wens

Music: Iris Van Geen

Dramaturgy: Nele Buyst

Production: Griet Dobbelare & Abel Provoost

Boat building: Boat building: Werner Musenbrock – The Workshop

photo by Michiel Devijver

photo by Michiel Devijver